By Mark Herr

Imagine you’ve passed your deadline for filing a report at work. The report isn’t finished and now you need to decide where you’re going to finish it. This is critical, because your boss hasn’t confronted you about it yet, and you just might get off scot-free if you manage to get it in soon enough. Here is the dilemma: If you work from home, you won’t see your boss and so won’t get a thrashing. Without running into you, your boss might not even recall the fact that you were supposed to submit the report, and you’ll get off free and clear. Your job fully permits you to work from home, but unfortunately you don’t have access to all of the company resources you need to get it done as efficiently as possible. It might take twice as long to finish from home, and if your boss already knows it’s missing you are going to be in even more trouble if it’s extra late. If you go into the office you’ll be able to finish the report in half the time and might get it submitted before anyone realizes it’s missing, but you’ll also risk the thrashing from your boss if he is aware. This is the type of situation that people encounter all the time: problems with multiple solutions, each with positives and negatives and no clearly superior alternative.

It just so happens that scenarios like these are common in nature as well, and how organisms respond to problems like these has important impacts on ecology and evolution. When we discuss the ways that organisms respond to problems like these, we refer to them as trade-offs: situations where an individual, population, or species gives something up in return for something else. It seems simple enough, but it turns out that this concept is tremendously important. For example, if a predator inhabits a landscape with diminishing prey resources, it may face a trade-off in how to respond. Some individuals may become more active in order to find more prey to sustain themselves, while others may take the opposite route and stop moving in order to conserve what energy they do obtain. In this way, a trade-off like this could result in one species diverging into two – an active forager and an ambush hunter.

This brings me to the research project that I’m going to be working on this upcoming spring and summer. I’ll be working with lab post-doc Chris Howey, who’s currently studying the way that proscribed fire impacts Timber Rattlesnakes here in PA. Chris is particularly interested in the impacts that these fires have on gravid (pregnant) female rattlesnakes.

So while I’ll be working with Chris helping him out on his larger project, we’ll also conduct a side project on the trade-offs that gravid female rattlesnakes make during the active season. Shortly after emerging from their winter dens, gravid female rattlesnakes will congregate in open rocky areas to incubate their developing embryos. Typically they stay at these spots, termed gestation sites, for nearly the whole active season – until they give birth to live young sometime in late summer. They are spending their time thermoregulating in order to develop their embryos as efficiently as possible, so it’s obviously important for them to choose sites with good thermal qualities.

This is where they might encounter a trade-off, though. The largest, most open rocky areas will have the most sun exposure, and so one would think they would be the best places for the snakes to choose as gestation sites. However, we think that these sites might leave the rattlesnakes even more exposed to predators than they would be otherwise – this is especially important because the snakes are already more vulnerable while out basking than they would be if they were foraging in the forest where their camouflage is most effective.

This past summer we found that some pregnant females chose smaller, more closed canopy spots with less sun exposure as their summer gestation sites. Why would these rattlesnakes be choosing sites like this when big open sunny spots are available? We think that this might be a classic ecological trade-off: with snakes weighing the thermal quality of the spots with the risk of being attacked by predators.

This might be what’s going on, or it might not. Perhaps the snakes are just choosing the spots that are closest to where they denned up. Maybe the closed spots and the open spots don’t even have different predation risks attached to them! We’re interested in exploring this issue to see if this is really what’s going on, and understanding this dynamic might help conservation authorities understand the ways that a species under threat (like timber rattlesnakes here in the Northeast) use the different parts of their habitat.

In order to test to see whether a trade-off really is occurring, we’ll be assessing the different gestation spots chosen by rattlesnakes for their thermal qualities and predation risk. To test the thermal quality we’ll analyze the sun exposure of these sites and we’ll place thermal models designed to mimic rattlesnakes and analyze them against the preferred body temperatures of live rattlesnakes that we measure in the lab.

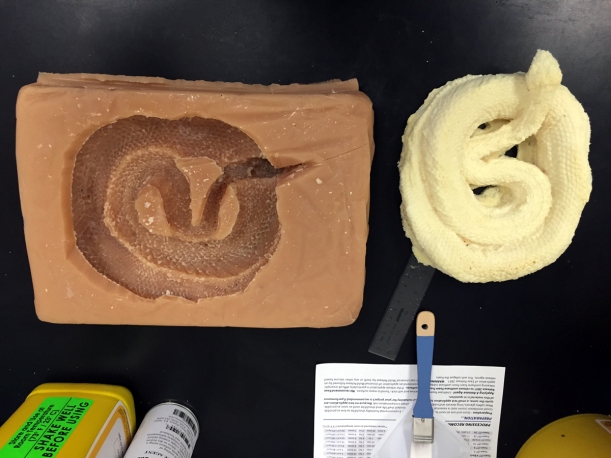

How will we measure predation risk? This is the part that I’m working on right now in preparation for this summer. We are making realistic foam rattlesnake models that we are going to set out at the different sites. The foam that we are casting the snakes in should hold the imprint of attack from the predators and should give us some idea of what type of predator went after our snakes! This is a technique that’s been used before (on rattlesnakes no less!) by Vincent Farallo to quantify the risk of predation, and we are excited to use it to test our hypothesis!

Making these foam models is taking up most of my time on this project right now, and we are going to need a couple hundred by the time spring starts, so I’m busy! I’ll post more updates on the project here on the Lizard Log in the future as we get rolling – but I’ll leave you off with some photos of the model making process that’s taking up my time now while there’s still snow on the ground!

The first step in making our models is to get an actual snake to cast them from! We took this preserved timber rattlesnake specimen from the teaching collection here at Penn State to make our mold for the future specimens.

Then we posed her in a typical basking rattlesnake position – getting the snake like that isn’t as easy as it seems! When specimens are fixed in formalin during the preservation process it tends to make them rigid and tough to work with, but we managed!

After this we poured a rubber mold compound in the tray and let it set, then we removed the preserved snake and voila – snake mold!

Here you can see we’ve just poured the mixture into the mold – it will then quickly expand to fill the whole mold and once it hardens…