Part 2 of 2 in the fence lizard fire ant saga: Rapid evolution of fence lizards (Sceloporus undulatus) in response to selective pressures imposed by red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta).

I’m a postdoctoral research fellow in the Langkilde Lab who studies the ecological mechanisms that result in evolution. My interests range from the evolution of life histories in response to climate change to behavioral evolution in response to invasive species to the evolutionary significance of culture. Most of my research, however, is on Sceloporus lizards (AKA Spiny lizards or Swifts), focusing on their genetic and plastic responses to environmental change and the underlying interactions between physiological (e.g. hormonal), behavioral (e.g. resource use and niche construction), and epigenetic mechanisms. My research endeavors have brought me to Costa Rica, Panama, Mexico, the subtropics of Florida, and inside Biosphere 2 in the Arizona desert, but I am currently focusing on lizard evolution in the southeastern US, which brings us to the current continued blog post.

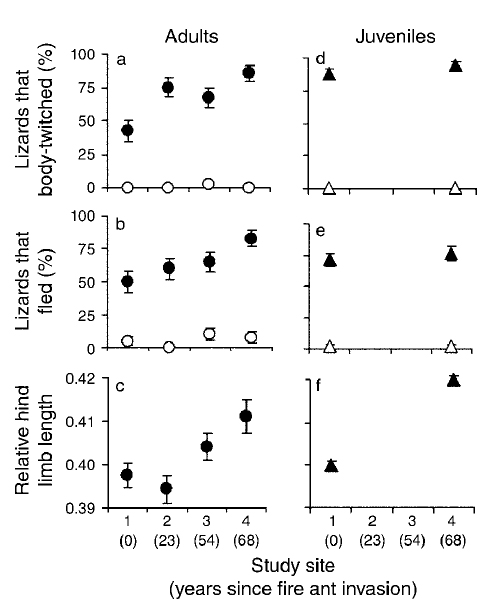

So, in the first chapter of the Saga we found out that fence lizards are adapting to habitats where they coexist with fire ants, which quickly find and attack lizards when on the ground. Some fence lizards dance and run away from fire ants when attacked, and the number of lizards that exhibit this behavior increases the longer a population has experienced fire ants. See the first chapter of the Saga here.

Fire ants attacking lizards is interesting, but what is even more interesting is that this interaction can be turned on its head! Ants are a normal part of a fence lizard’s diet, so why wouldn’t fire ants be susceptible to being eaten by a fence lizard? Fire ants are susceptible! We’ve noticed while in the field that fence lizards do occasionally eat fire ants during encounters. Not surprising, until you pick up a little insider information about a strange twist. One of Tracy Langkilde’s studies revealed that eating fire ants can decrease lizard survival!

If it is bad for lizards to eat fire ants, why do they do it? In light of what appears to be evolution with regard to the dance and run behaviors, we hypothesized that fire ant-eating behavior of fence lizards should be less frequent in populations that have experienced fire ants for a longer time (i.e. more generations). We tested this by recording fire ant consumption during staged encounters between fire ants and fence lizards from both fire ant invaded (experienced) and uninvaded (naïve) lizard populations. We also tested both juveniles and adults because we knew that they have a tendency to respond to fire ants differently.

We found a complex relationship that somehow supports both what we already knew from previous experiments (adults in fence lizard populations are adapting to the presence of fire ants) and our newer hypotheses about juvenile lizards adapting to the fact that eating fire ants can be toxic! It seems that adult fence lizards from populations that have been coexisting with fire ants for a long time eat fire ants much MORE frequently than lizards that have never experienced fire ants. What!?

Fire ant consumption by lizards. The proportion of field-caught (a) and laboratory-reared (b) adult (open squares) and juvenile (solid squares) fence lizards, Sceloporus undulatus, from a fire ant-invaded and uninvaded site that consumed fire ants during fire ant attack. Points represent mean values ± 1 standard error.

Figure – Robbins and Langkilde 2012 J Evol Biol 25(10):1937-46

We also found, as we hypothesized, that juvenile fence lizards from populations that have been coexisting with fire ants for a long time eat fire ants much LESS frequently than their inexperienced counterparts. So we see changes in feeding behavior in fence lizards after fire ants invade their habitat, just like we saw with the dance and run anti-predator behaviors. What is more fascinating, however, is that our results with regard to feeding behavior suggest what is called an ontogenetic shift in selection pressures. That is, it is more adaptive to behave one way while young and then behave the opposite way when older! Fire ant invaded habitats select (via natural selection) juveniles that do not eat fire ants, but can learn to eat fire ants once they grow up!

Next, obviously, we wanted to test if and how well juvenile lizards learn to eat fire ants. Our hypothesis for this experiment was actually that the lizards would learn NOT to eat fire ants because they get stung in the mouth when they eat them. At some time during their life with fire ants they seem to learn to eat fire ants, but we thought it would be after they were adults because fewer juveniles from the invaded site had eaten fire ants when on the mound and under attack (see above).

We were wrong! When it comes to eating fire ants, the longer lizards are exposed to fire ants the more lizards eat them!

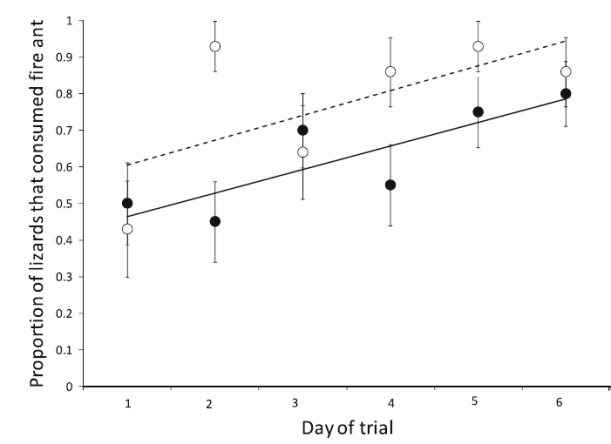

Proportion of lizards from invaded (open circles and broken line) and uninvaded (solid circles and solid line) populations that ate a fire ant over a 6-day period. During this period lizards were fed 1 fire ant followed later by 2 crickets each day, representing a subsistence diet. Points show proportions ± 1 standard error.

Figure – Robbins et al 2012 Biol Inv 15: 407-415

We even found that more juvenile lizards from the invaded site ate fire ants during the experiment than those from the uninvaded site (lizards naïve to fire ants). So, juvenile lizards appear to learn to eat stinging ants pretty quickly when they are not on a mound being attacked! It changed from 50% to 80% of lizards eating fire ants within 6 days. Maybe fire ants are addictive like hot sauce is for us! Endorphins can be powerful rewards.

I know, it’s a little confusing. Juveniles from invaded sites (i.e. that have experience with fire ants) eat fire ants less often when on the mound being attacked (first graph), but more often when fed one ant each day over a 6 day period (second graph)? Well, the two scenarios are a little different with a lizard being under attack by many fire ants in the first and in the other only being exposed to one lonely fire ant. And that may have something to do with the it.

The effects of envenomation are mass dependent, so the fact that juvenile lizards are small means that they can be overcome by fire ant venom faster than adults. When a juvenile lizard is on a fire ant mound and notices many potentially stinging ants, it doesn’t think to eat them as much as it thinks to dance and run away. However, away from fire ant mounds fire ants are often an abundant potential food source. When fire ants invade habitats they pretty much take over and push out many of the other arthropods that otherwise serve as food for lizards. Although eating fire ants can increase the chances of a lizard’s early demise, eating a few fire ants here and there will not overtly harm all juvenile lizards. Even in the study that found an increase in mortality after eating fire ants there was still a 66% survival rate. So, because venom effects are mass dependent, it’s possible that juvenile lizards that survive and grow up (and thus get bigger) can eat more fire ants (and get stung) without feeling the negative effects of fire ant venom.

Although natural selection appears to select juvenile lizards that do not eat fire ants when being attacked, it seems they like to get stung in the tongue as they become less young! But this tale has yet to be completely sung! We only fed the lizards 1 fire ant per day, which may not be enough to make them learn to avoid eating them. They may easily forget what they had for breakfast yesterday and thus need to experience eating and getting stung on the tongue a few times a day to learn to avoid eating fire ants. Or not. We are analyzing experiments we designed to test just that right now!

So the saga continues . . .

Sometimes it’s a little frustrating to experience how unfamiliar amateurs are with snakes. I love snake identification questions because they’re always so humorous. You can ask people practically anything, anything, and they’ll agree that their snake had the feature. Was it brown? Yes. Was it black? Yes. Did it have a big, purple, protruding snout? Er, I guess so, yes. I used to volunteer to field calls when I was at the Atlanta Zoo, hoping to accumulate excellent stories. Inevitably, I’d talk them through their snake’s features and it would always converge on a brown snake with stripes and a diamond-shaped head, and this would always be identified by the caller as a Copperhead. I always asked them to send me digital photos, and the snake would inevitably turn out to be a harmless

Sometimes it’s a little frustrating to experience how unfamiliar amateurs are with snakes. I love snake identification questions because they’re always so humorous. You can ask people practically anything, anything, and they’ll agree that their snake had the feature. Was it brown? Yes. Was it black? Yes. Did it have a big, purple, protruding snout? Er, I guess so, yes. I used to volunteer to field calls when I was at the Atlanta Zoo, hoping to accumulate excellent stories. Inevitably, I’d talk them through their snake’s features and it would always converge on a brown snake with stripes and a diamond-shaped head, and this would always be identified by the caller as a Copperhead. I always asked them to send me digital photos, and the snake would inevitably turn out to be a harmless