New paper in Journal of Zoology featuring Kirsty, Tracy, and Nicole! The substrates on which animals spend their time can affect how they look, move, and sound. We found fence lizards more frequently on deciduous trees, on which they sprint faster and produce less noise relative to coniferous trees, which may affect their ability to catch prey or evade detection by predators. Noisiness and performance have received less attention in the context of substrate preferences than visual camouflage, but our results suggest they may also be important in determining the surfaces on which lizards prefer to be. (Check out the paper: Tree selection is linked to locomotor performance and associated noise production in a lizard.)

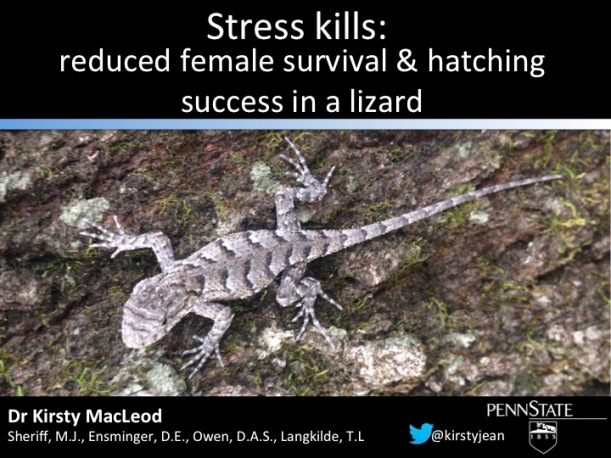

In the summer of 2016 I began a large-scale experiment investigating the effects of maternal stress on offspring characteristics in the eastern fence lizard, Sceloporus undulatus. My primary mission for the first part of that summer was simple: catch as many lizards as possible in the longleaf pine forests of southern Alabama. When you spend most of your day pursuing a small prey species, you quickly start to think like a predator. In what areas are you most likely to find them? At what times? On what surfaces? The cumulative years of experience of my fieldwork team (colleagues from the Langkilde lab) suggested that fence lizards were mostly found where there was a mix of hardwood deciduous trees and pines, and that they preferred the deciduous trees, like oaks and hickory, to the famous pines of the region. The longer I spent looking for lizards, the more I noticed that this observation held true. I didn’t put much thought into why until one day when I followed a lizard into a small stand of pine trees. I momentarily lost sight of the lizard, until I heard a loud scrabbling from a few metres away – there was the lizard, scuttling up a pine tree on the smooth, dry flakes of its bark. If the noise of the lizard’s claws moving on the pine bark alerted me so easily to its presence, I thought, perhaps the same was true for its real predators! Also – perhaps that noise was indication that this type of bark, with fewer crenulations and ridges on which to grip, was more difficult for the lizard to run on. Together, could these provide a reason that fence lizards seem to avoid pine trees despite their prevalence?

We decided to test this in the field. First, we quantified whether our anecdotal hunch that lizards prefer deciduous trees to conifers (pines) was really true by conducting thorough searches for fence lizards throughout our field sites, and noting the tree type we found them on, as well as the availability of trees in that area. This allowed us to test whether lizards were “choosing” deciduous trees in areas where they could also choose pines, as opposed to just being found in areas with only deciduous trees. As we expected, we found that even when availability of coniferous:deciduous trees was more or less 1:1, lizards were overwhelmingly found on deciduous trees, not pines.

Next, we tested our hypotheses that tree type changes how noisy lizards are when they move, and how quickly they are able to move. We did this by releasing wild lizards on either coniferous or deciduous trees, and then recording them as we stimulated them to run upwards on the tree by gently tickling their back legs. We then analysed these recordings and found, as we predicted, that the noise of lizards running (the sound level they produced when running compared to the background noise when they were still) was significantly higher when they were running on the smooth, flakier bark of coniferous trees. We also found that the sprint speed they attained on coniferous trees was lower than on deciduous trees. In other words: they are noisy and slow on pine bark compared to the bark of trees like oaks and hickorys.

Studies investigating where animals spend their time (either in terms of broader habitat preference, or more localised use of substrates) has often focused on coloration, and the camouflage it may or may not afford. Our study shows that other aspects of camouflage, such as acoustic camouflage, may also be important. It’s also important to consider how substrate affects performance, like sprinting speed: once you’re spotted by a predator, the speed at which you’re able to escape may be just as important as trying to remain hidden in the first place.

This was one of my favourite studies to be involved in, for a number of reasons! First, I love that we were able to find ways to test hypotheses based on a very simple natural history observation. Understanding the natural history of an organism is crucial for developing new ideas – and the “why does this happen?” questions are the bedrock of behavioural ecology. Second, this study was an opportunity to bring together friends and start new collaborations! Langkilde lab alum Nicole Freidenfelds brought her great knowledge and understanding of herpetofauna and natural history; local friends in Alabama helped me to identify tree species; I knew of Gavin’s prowess in acoustic analysis through Twitter, and asked him to help with this aspect of the project; and Tracy and I had a blast exploring these ideas with them!