In August, my two older brothers and I went to Komodo National Park in Indonesia for a week of scuba diving and backpacking.

Departing the plane in Surabaya: this photo was actually taken midmorning. The hazy skies are due to smoke from the rampant slash and burn agriculture which is devastating virgin forests on Borneo and other islands.

Going to see Varanus komodoensis in Indonesia was most certainly on my herp bucket list, and so when my older brothers mentioned that they wanted to take a trip somewhere and Komodo was an option, I naturally jumped on it. My brothers wanted a place where we could backpack and also go scuba diving, and it turns out that Komodo has some of the most beautiful coral reefs in the world. Komodo National Park consists of a series of small islands (Including Komodo and Rinca, where one finds the dragons) between the relatively large islands of Flores and Sumbawa. It is a part of the Lesser Sunda Island chain. The Lesser Sundas are bio-geographically fascinating. They essentially form an arc of mid-sized islands directly to the east of Java – extending almost to Papua New Guinea. On the far western end of the arc is Bali – a popular vacation destination. Incidentally, we had a longer than expected layover in Bali on our way to Flores: Mt. Raung in eastern Java erupted while we were in the air and disrupted air traffic through the whole region. We had a mid-air reroute to Surabaya on Java and then barely made it into Bali where we missed our outgoing flight! We managed to get onto a standby flight early the next morning, though, and our schedule was left essentially intact.

Directly to the east of Bali is the Island of Lombok. Between these two islands runs the famous Wallace Line. The Wallace Line is the biogeographic barrier between the Asian and Australian Faunal regions. It was first identified by Alfred Russell Wallace – one of my professional heroes. Wallace collected zoological specimens throughout Indonesia, and I re-read his incredible travel memoir The Malay Archipelago during this trip.

Of all the Lesser Sunda Islands, only Bali is on the Asian side of the Wallace Line. However, the line is not a clean break. If it were, one would expect to go from seeing tigers and elephants in Bali to kangaroos and wombats on Lombok. This isn’t the case. While there actually are tigers on Bali (at least there were until they were hunted to extinction in the 20th century), crossing the Wallace Line instead takes you into a sort of transition zone between the true Asian and Australian faunal regions. A place where one can find a bizarre mix of species – like cockatoos flying over herds of native wild boar – as well as endemic species like the Komodo dragon. This region is referred to as Wallacea.

Incidentally, it isn’t just a transition point in terrestrial biogeography. The incredible biodiversity of Komodo’s reefs is due to the fact that the National Park lies at the interchange between the Pacific and Indian Oceans – resulting in an incredibly biodiverse marine ecosystem as well. The diving was incredible – but I’ll stick to the herp stuff for this blog entry.

The vacation was spent on a live-aboard dive boat, and we spent days alternating diving and trekking (really mostly just herping on the Islands!). We went on 2 big hikes, the first on Rinca island where we found the majority of the cool herps for the trip. The second was a 2-day hike to Mt. Satalibo, the high point of Komodo Island. We spent the night camping on the summit and then bushwhacked down to the tiny ranger station at Sebita where we were picked up by our dive boat’s zodiac.

Before either of those scheduled hikes, though, we had some downtime between dives. We were quite close to Komodo Island, and even though it was midday and blazing hot, I couldn’t help myself from getting on land. I asked Andrew and Daniel if they wanted to come with, and they said yes – so I directed one of the crew members to fire up the zodiac and drop us off for 30 minutes or so. He thought we were crazy to go on the island by ourselves but dropped us off just the same!

Daniel and Andrew in the grassland on Komodo with their sticks for defense! I had assumed – correctly – that we wouldn’t encounter any dragons with the midday sun beating down on us like it was.

Daniel and Andrew with the dinghy in the background. The tan and gold colors of the islands contrasted beautifully with the blues and greens of the surrounding ocean.

That night we went to a spot frequented by the dive boats in the area. The mangroves are packed with flying foxes – and there were thousands of them! Each one of the dark flecks in the sky in this photo is a fruit bat leaving the mangroves and headed to forage in the moist forests on nearby Flores.

The next day we began our first hike on Rinca Island. Rinca and Komodo are home to the majority of the dragons in the world. I was excited to finally get in some serious herping. Our first spotting was a mammal though: a semi-aquatic crab-eating macaque in the mangroves by the dock.

First dragon of the trip! This was a juvenile dragon basking in the morning sun by the ranger station. Like deer by any National Park headquarters in the US, the dragons near the ranger stations on both Rinca and Komodo were habituated to humans. Once we got off the common tourist trails we found that the lizards acted much differently.

We waited for our guides and then set of on a hike across the island. Although we’d set everything up ahead of time, when we actually got there none of the professional guides wanted to go on the hike that we’d scheduled – it was too long! It took some negotiating, but we finally got some guides that were willing to take us on the planned route.

I started flipping logs and rocks along the trail looking for herps. Our guides were laughing at us and told us that they see snakes only very rarely. That might be true, but it only took us a few minutes on the trail before we’d found our first snake.

I glimpsed a snake slithering in the cracks of a dried-up buffalo wallow. I grabbed it with the tongs and there it was – my first ever live Elapid!

I quickly tubed the snake (wearing sunglasses!) and showed the guides – who at this point were past the “Americans are INSANE” stage and into the “Wow this is actually really cool!” stage. This was their first time touching a cobra, and they loved it! Showing people that snakes are something to be respected and admired, rather than feared, feels awesome.

The spitting cobra lived up to its name and doused my go-pro while I was getting some close up footage!

Water buffalo spending time in a pool during the heat of the day. Our guides told us that this pool was one of the few that didn’t dry up completely in the dry season, making it a favorite ambush spot for hungry dragons.

I flipped this gecko underneath driftwood. I’m totally unsure about the species, but I think it’s a species in the widespread genus Cyrtodactylus.

This giant centipede was under the same piece of driftwood as the gecko! Unfortunately I don’t have anything good to show the scale but the centipede must have been 9-10 inches long. Easily more terrifying than the cobra – and quite capable of making a meal of the gecko!

After a full day of diving my brothers retired to eat some dinner. I still had energy, and we had anchored off of Komodo Island – where we would begin our hike early the next morning. I hopped on the dinghy and went to see what I could find at night and found this gecko foraging in the intertidal zone! I think that it’s a Hemidactylus of some sort.

After returning to the boat with a single herp for the night, I was ready to eat some food and drink some beers and get ready for the following day. Incredibly, I would get one more herp for the night back at the boat!

With tongs at the ready, we managed to get this banded sea krait! She may have been attracted to the boat’s lights.

The crew told us that the local lore said that it was good luck to have a sea krait swim up to a boat. This boat was new and it hadn’t happened yet – so the captain was particularly excited! It was his first time touching a snake of any sort, and definitely the first time one had been on his boat!

The next day we began our trip to the top of Mt. Satalibo. For reference, almost nobody does the hike we did. The head ranger managed to scrounge a tent that they give to film crews to use on the porch of the ranger station to keep bugs away. What we did is definitely not part of the normal menu – and by the time we made it back to the boat the next day we were well aware of why that is.

This was the first non-habituated dragon that we encountered. I was amazed by how curious it was. Curious in a predatory sort of way. I absolutely don’t want to be sensationalist, but the fact is that the dragon saw the group of us and immediately began a slow and steady walk towards us. When it got particularly close, the guides repeatedly hit it in the head with their forked sticks. In response, the dragon backed up and then tried to circle around and come from a different angle. It was a fascinating experience. The dragon wasn’t sprinting at us – it was merely walking. However, I have no doubt that if we were to stand still and allow it to approach, that it would have sunk its teeth into one of our legs. It wasn’t in a rush like we normally see predatory encounters, so it was an alien experience – but I am quite certain that that dragon wanted to eat us. That obviously doesn’t make it malicious, but the experience is one that I cannot get out of my mind. It simply wanted to eat us if we didn’t cause much trouble. As it was, the guides hit it in the head several times (which I am led to believe is standard procedure), and eventually it retreated and stared as we walked away.

Soon after encountering that dragon, the bushwhacking became incredibly difficult. I have had the privilege of going through some thick and thorny vegetation during my research in the lab. The “Blue-creek hell hole” that lab alumnus Sean Graham and I went through to collect Cottonmouths comes to mind. I can say that without a doubt, the bushwhacking on Komodo Island was the worst I’ve ever been through. I want to come up with a way to describe the horrible-ness of the Thorn Forest on that island, but I cannot. Anything that I could write about it would detract from the reality of how bad it was.

After the “Thorn Forest” we arrived the highest elevation forest type. The late Walter Auffenberg wrote several lengthy monographs about Komodo dragons and the herpetofauna of Komodo Island. While he was curator of Herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, he decided that he wanted to research Komodo dragons. To accomplish this, he simply moved with his wife and small children to Komodo Island and began research! His writings made up the bulk of my pre-trip research. He categorized the vegetation communities on the Island and referred to this semi-moist forest as Quasi-Cloud Forest. It was clearly distinct from the lower elevation forests – with more evergreens and bromeliads indicating a wetter environment.

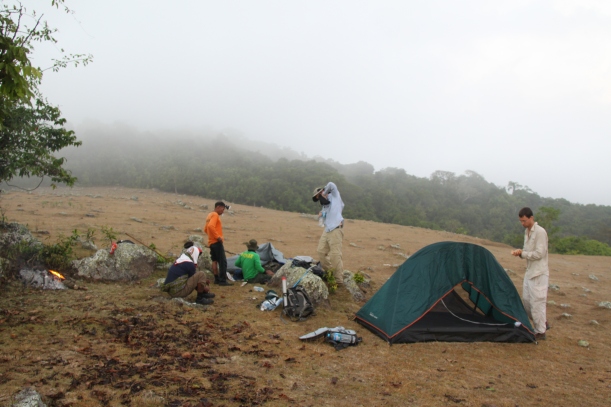

We reached the top of Mt. Satalibo and set up camp. Backcountry camping on Komodo is something that almost nobody does. Once we set up camp and got a fire going, I actually asked the guides how frequently they camp on the island with tourists. The answer was something like “We did it one time with a crazy Dutch guy like 5 years ago.”

At about 1am I gave up sleeping. Naturally, I hadn’t brought any cold weather gear on our Komodo Island hike, and it was amazingly cold up at the top. First I, then Daniel, surrendered and just spent the rest of the night huddled with our guides by the fire. Somehow Andrew managed to sleep through the whole night. Once it got light enough we began our hike down. The plan was to hike from where we had camped on Satalibo down to the small ranger station of Sebita. We had scheduled things rather tightly and had a flight to catch in the afternoon but figured that we would be able to make it down to Sebita relatively quickly.

I’ll just say up front that we did not make our flight. The bushwhacking the day before had just been a taste. I knew we were toast early on, when I checked my GPS and found that 2 hours into our hike we had made it a grand total of 750 meters. We spent hour after hour going through a thorn forest that – like before – I won’t try to describe based on principle. Everything had thorns. Every branch, every tree trunk, every vine. There was one single tree species that had no thorns; I remember it vividly: at even the lightest touch it would hemorrhage black ants that would cover everything. I was stung early on in the hike, and hours later my arm still throbbed.

We spent hour after hour hiking through an endless thorn forest, going prone for significant stretches when it was too thick to crouch or crawl on our hands and knees. Turns out that when the guides had “done this before” with the Dutch gentleman that they had gone back down the way they came to the main ranger station – not to Sebita. This was everyone’s first time doing this bushwhack. At the utter mercy of the Island, I started laughing at the hilarious helplessness of our situation. There was nothing to be done but push through the thorns and the ants until the end. It was the most difficult day of hiking in my life so far, but I am glad we did it. My respect for the ecology of that island is utterly cemented.

After making it to the ocean we got on our boat and figured out flights for the next day, I even managed to make it home in time for one final week of field work in Pennsylvania before the semester started!