My name is Shawn Snyder and I am currently a senior majoring in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. This is my first and only year working in the Langkilde Lab. During the summer of 2016, I worked under Dr. Chris Howey as a Research Technician studying the effects of prescribed fire on timber rattlesnake populations. This position provided me the opportunity to radio-track timber rattlesnakes, record habitat data on tracked snakes, catch new snakes (extremely fun), learn how to safely tube a venomous snake (even more fun), and conduct vegetation surveys. Also, this position provided me the opportunity to formulate my own scientific question to test! Together, Chris and I thought up a small side-project that I could conduct throughout the summer, which provided me the fantastic experience of going through the scientific process, collecting my own data, analyzing those data, and now writing a manuscript so that I can share those results with the scientific world.

When we first started collecting data for my side-project I was a little apprehensive. Once the data was collected and analyzed I realized that this project was going to take time and a large amount of effort to complete. As the process of analyzing the data and then coming up with a plan for the manuscript began to take shape, I started to feel challenged and nervous by this new task. But weekly meetings with Chris to discuss the process of writing a manuscript have helped immensely. This is my first manuscript and yes it is challenging, but it will all be worth it once we have a finished product. I have ambitions to continue on to a Graduate program after I graduate and this manuscript will help me build my C.V. to apply to Grad schools.

Two yellow morphs bask alongside three black morph timber rattlesnakes at a gestation site. Although we did not use gestating (i.e., pregnant) females as part of this project, this shows you the posture of a basking snake and the difference in color morphs.

My research is investigating if the two distinct morphotypes of timber rattlesnakes (a dark, black morph and a lighter, yellow morph; see above picture) use basking habitat with differing amounts of canopy openness and solar radiation. Previous research suggests that the dark morph evolved in response to thermal limitations in the northern parts of its range. Darker snakes have more melanin in their skin, which allows them to absorb more solar radiation and maintain a higher body temperature than yellow morphs. Yellow morphs having this thermal disadvantage, in theory would have to choose basking sites that receive more solar radiation to compensate for this limitation if they wanted to maintain a similar body temperature to the black morphs. Specifically, I am testing the hypothesis that yellow morphs use basking habitat that has more canopy openness and receives more direct solar radiation (i.e., sun) than basking habitat used by black morphs.

A black morph male timber rattlesnake is seen courting a basking yellow morph female. Once again, the difference in color morphs is striking and has led many to ask what selective pressures are maintaining this polymorphism.

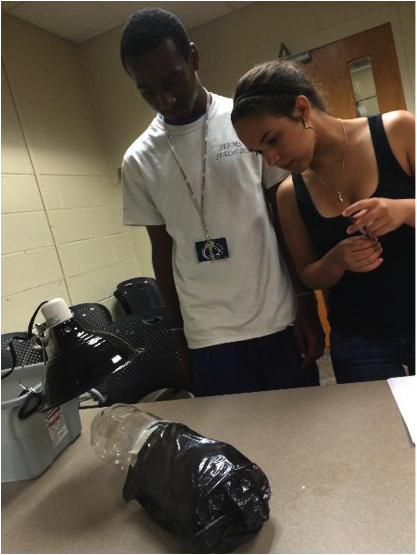

To test this hypothesis, I measured canopy openness over basking yellow and black morphs. I used the timber rattlesnakes that are being radio-tracked for Dr. Howey’s main study as my sample population and placed a flag where a snake was found exhibiting basking behaviors (see picture below for example). We took a picture facing skyward directly over the snake using a camera with a fisheye lens. This lens takes a picture of 180 degrees and captures an image of all of the canopy over the snake (see picture). We can then analyze these hemispherical photographs using a computer program called Gap Light Analyzer to measure the percent canopy openness and the amount of direct solar radiation transmittance (i.e., rays of sunlight) for each basking site. Direct solar radiation is when the sunlight reaches the forest floor with no obstructions from the canopy; as opposed to indirect solar radiation which may be radiation that is being reflected off of clouds, trees, or the ground itself. Our study site is characterized as having a mature Oak/Maple forest with an abundance of closed canopy throughout the area. Both morphotypes use this “closed canopy” forest throughout the summer as foraging grounds, and when they need to bask they must seek out areas where some sunlight is making its way through the canopy. This is where my question becomes very important comparing the habitat used by each morph.

A flag is placed next to a basking yellow morph. An exact description of the habitat is recorded so that I can come back at a later time (when the snake is not there) and take a photo of the canopy directly over where the snake had been.

Two examples of hemispherical photographs taken over two different basking timber rattlesnakes. Both canopies actually have similar canopy openness, but the canopy on the left receives far more direct solar radiation based on the placement of those canopy openings.

So far, my results show that the two morphs use habitat that have similar percent canopy openness, however, there was a difference in the amount of UV transmittance between the basking sites used by the two morphs. Canopy openness doesn’t necessarily designate a “warmer” site because the sun path may not go directly over the gaps in the canopy of that site, thus, the site wouldn’t receive large amounts of direct solar radiation. Black morphs use basking sites that received lower amounts of direct sunlight. They may be able to do this because the greater amount of melanin in their skin provides a greater ability to absorb whatever direct or indirect solar radiation is available more effectively. Yellow morphs use basking sites that received more direct solar radiation. They could be forced to use these sites to compensate for their disadvantage in their thermal ability. I am currently working on writing a manuscript for these data and hope to have it completed by the end of 2016. Stay tuned for more on this manuscripts progress!

Here is a picture of Shawn (holding a Hellbender!!) while on a break from collecting some amazing data.